This is the last of a five part story of the Five Emperors who underpinned the greatest period of peace in ancient history: Pax Romana.

Among the chronicles of successful Roman rulers Marcus Aurelius stands tall with the all-time greats. With the exceptions of Augustus, Trajan, Aurelian, Diocletian and Constantine there was perhaps no emperor more capable of governing Rome than Marcus. A precocious talent first sighted by Hadrian nearly 3 decades before his own rise to power, the story of Marcus Aurelius is a tale of overcoming odds, enduring betrayal, persevering through hardships, and family tragedy – a fitting conclusion to Rome’s golden age. Marcus is also my favorite Emperor and an inspiring leader that set great examples for me.

Raised in an era of peace but presiding over one of the most tumultuous periods of the Empire, Marcus Aurelius inherited a prosperous nation heading for disaster: wars, disease, and conspiracy plagued his rule. Some of these events occurred due to long term negligence of his predecessors, some were just overdue. Antoninus’ neglect of the Parthians in the east and the Marcomanni in the north cultivated a sense of complacency within the state, and it was up to Marcus to redeem Roman honor. The once embraced notion of international and state-wide trade networks also came under strain during the Aurelius years as plague gripped the Empire and proliferated through interconnected trade routes. In this era of unprecedented challenge Marcus rose to confront it head on – nearly his entire Imperial rule was spent outside of Italy where he fought against foreign invaders.

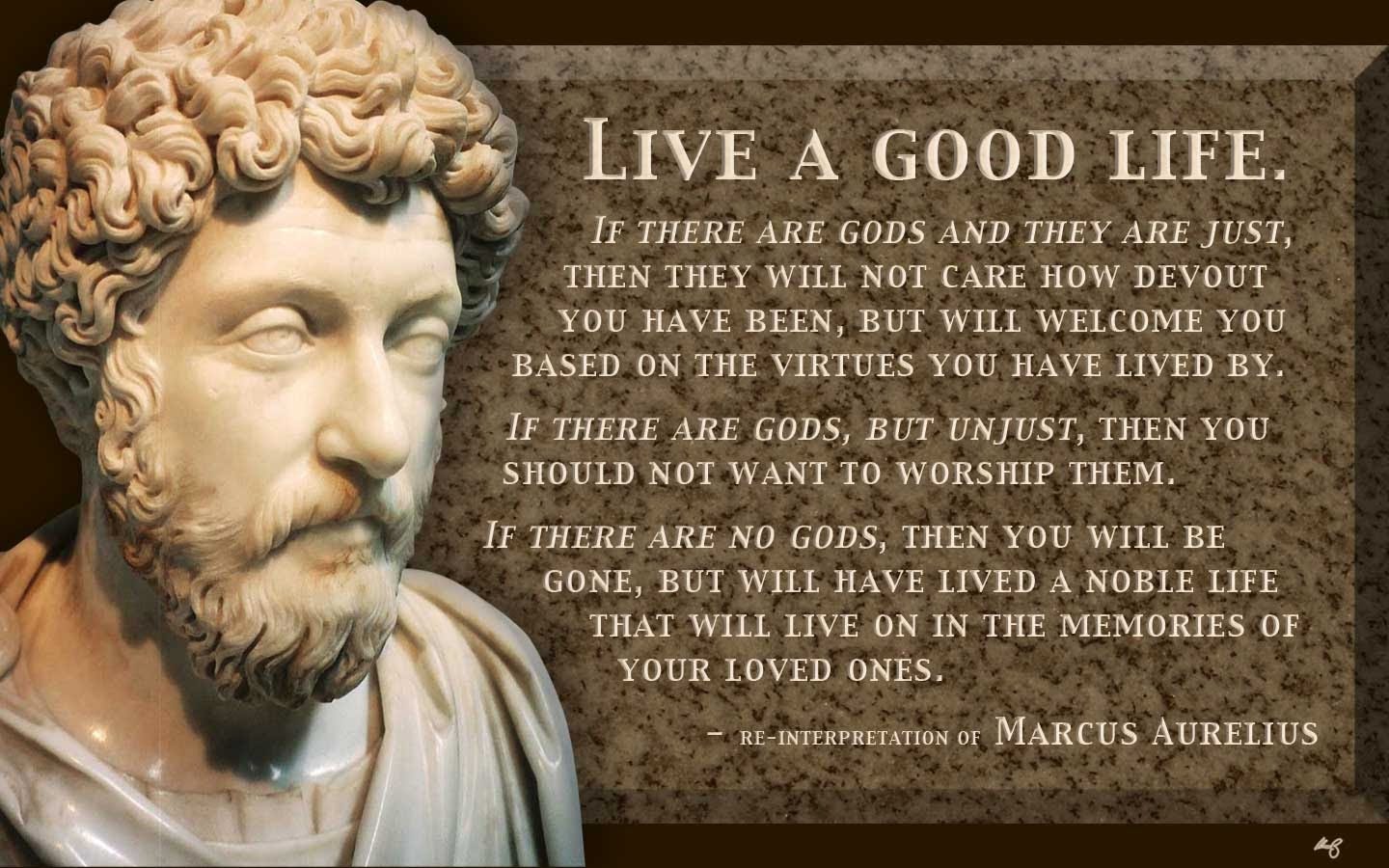

Yet during these unstable times the Emperor did not forget who he was; Marcus was famously referred to as the Philosopher Emperor due to his love for philosophy and his writings which would later be compiled into a book called Meditations. He was well-known for his Stoicism: an ancient Greek school of philosophy that emphasized logic and self-control, to accept the world as it is and not let negative emotions such as anger take hold of actions. Marcus believed and espoused these ideas daily; during his reign as Emperor he would make consequential decisions based on these rules. He was a great ruler but a flawed man and it was this imperfection that would ultimately lead to the end of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty and accelerate the decline of Rome. In this final part we’ll look into the legacy of Marcus Aurelius – the last great ruler of Pax Romana.

Marcus Aurelius

Period of Rule: 19 Years

Predecessor: Hadrian (Nerva-Antonine Dynasty)

Successor: Commodus

The Young Prodigy

Like many of his predecessors in the Pax Romana Marcus’ family originated from southern Iberia in what is now Cordoba. Born as a sickly child he was raised in a loving family but plagued with various illnesses that would follow him for the rest of his life. Marcus had a sister Annia Faustina and his father passed away very young at the age of 3; following this tragedy his mother decided not to remarry and Marcus was sent to the care of nurses and tutors. It’s not really clear how they met, but at a very young age Marcus caught the attention of Emperor Hadrian who subsequently declared his father-in-law Lucius Caesar successor. Hadrian’s plan was to bide time for Marcus to grow up and take the throne in his 20s but this did not work out as intended and Antoninus Pius took the role instead, adopting Marcus and his brother-in-law Lucius Verus. After being adopted by Antoninus his claim to the throne was further solidified with a remarriage to Antoninus’ daughter Faustina the Younger.

The life of an heir to the Roman Empire was a privileged one and Marcus’ was no exception. He was gifted with the best education and tutors of his day and credits many of his own success to his two tutors Herodes Atticus and Marcus Fronto who taught Greek and Latin respectively. The two tutors had a tense relationship with each other due to differences in personality but they shared a curious commonality: a dislike for philosophy. Thus it was a surprise to most of his teachers when Marcus later took up the study of philosophy and fashioned his lifestyle around it. Marcus’ teacher Quintus Rusticus taught philosophy and was the one who introduced Stoicism to his life which he was greatly thankful for in his autobiography. His passion for learning and philosophy would carry with him his entire life: he later studied under Sextus of Chaeronea even as an elder Emperor at the end of his life.

Due to Hadrian and Antoninus’ long lifespans Marcus as able to accumulate a wealth of experience in government even before donning the purple robes of the Emperor. Thanks to Hadrian he was able to skip the minimum age requirement of 24 to hold a political position and got a head start relative to his peers. In his various administrative roles he learned how much paperwork was involved in being a leader and found it difficult to reconcile his privileged life with his humble habits dictated by Stoicism. He also found his poor health a major hindrance in his ability to govern and realized he would have to deal with these challenges for the remainder of his life.

These early stories paint Marcus’ life as a man who was raised to be a leader, but deep down had doubts about his own desire to rule. He was much more passionate about philosophy and living a simple life; he disliked the displays of grandeur and public speaking required of a politician and yearned for knowledge and peace instead. Ironically one of the only few things that kept him devoted to his duty was the Stoic philosophy his teachers had always disliked.

A Tale of Two Emperors

In 161 Antoninus Pius finally drew his last breath and at the age of 40 Marcus became Emperor. Although Antoninus had declared him as his successor Marcus felt obligated to honor his grandfather Hadrian’s wishes for Lucius Verus and Marcus to rule together. Upon his ascension Marcus refused to accept his responsibilities unless the Senate would also nominate Lucius to be his co-Emperor which the Senate had no choice but to agree to. Lucius Verus was quite the opposite character of Marcus; he was loud, aggressive, and preferred playing sports, watching gladiator fights, and drinking rather than learning about the subtleties of politics. Despite their differences there was never any indication of disagreements between the two; Marcus was the obvious senior Emperor in their partnership and Lucius agreed to it willingly. In fact the first few months of their joint rule was peaceful and productive; the Emperors were popular in Rome and promoted free speech. They also jointly assisted various towns in Italy that were affected by river floods that year and earned the support of the Senate as well.

Horsemen of the East

Peace unfortunately would not be the defining characteristic of Marcus’ reign; less than half a year into his reign trouble had begun to stir. In the east Rome’s eternal rival and great power Parthia had been biding its time for Antoninus to pass away and decided that now was the perfect time to strike. The Parthian king Vologases IV marched into the Roman client state of Armenia and removed the ruler in 161, replacing him with a Parthian puppet instead. To make matters worse news then arrive of Vologases’ plans to march south into Roman Syria, threatening a major rebellion.

Since Syria was a major component of the Roman trade network, Marcus began to realize the seriousness of the situation and found his own military expertise lacking. Instead he summoned Lucius to Syria believing an Emperor who could personally direct the Parthian war would have much better results. Meanwhile Marcus would stay in Rome managing the affairs of the wider Empire; by redirecting his legions to the East his defenses to the west had weakened and he was keen to avoid two wars.

Lucius Verus unfortunately didn’t turn out to be the hard working ruler Marcus was; he spent most of the wars in luxury within Antioch and never even saw battle. There were rumors that he spent most of his days gambling and watching plays while his commanders did the heavy lifting. One such leader was Avidius Cassius, a prominent general stationed in modern-day Serbia who would lead his legions and achieve scores of victories over the Parthians. It was Avidius’ legions who fought back the Parthians and eventually retook the two famed cities in Mesopotamia: Seleucia and Ctesphion. The latter was the former capital of the Seleucid Empire and was a city that thrived during the past century, and the latter was the capital city of the Parthian Empire. According Imperial commands Avidius invaded Ctesiphon and burned the royal palace thus ending the Parthian wars for good. However a subtle misunderstanding led to the sacking and pillaging of Seleucia as well, a friendly Greek-dominated city who had openly welcomed the Roman legions only to be looted. This blemish on Lucius’ otherwise successful war would later come back to haunt him.

The Silent Killer

Unbeknownst to the two Emperors the conflict with Parthia brought back more than just riches and glory; in the ransacked city of Seleucia whispers of a deadly disease had begun to spread among the legions and citizens. The disease shortly erupted into a global pandemic within a few years when the Legions left the Far East and brought the plague back west and settled down into their garrisons.

The Antonine Plague as it’s referred to now was one of the deadliest pandemics in Roman history. Even now historians aren’t quite sure what it actually was or where it came from – some suspect it originated from as far as China or India and was carried to the west via trade routes in the Middle East. Once it arrived in Seleucia and was contracted by the Legions it spread rapidly across the Empire as sick men marched west back to their camps. Further expounding the problem were the vital trade routes in the Empire; the plague was carried by sailors and traders who traveled across shipping lanes and roads bringing the disease into major cities and finally Rome.

The plague was deadly as it was widespread; at its peak 2000 people died per day in Rome with a mortality rate of 25% and the hardest hit regions were concentrated in major cities. Across the empire the numbers were even worse: approximately 5 million people died from the plague which amounted to just under 10% mortality. The Legions were decimated by the plague as well since the disease spread rapidly among the soldiers and festered in the camps. Recruitment numbers dropped drastically and the Empire was dealt a huge blow to its national security.

International trade hemorrhaged as businesses closed down trade routes and roads in an attempt to contain the plague. These attempts severely weakened the Imperial treasury, robbing the state of tax revenues which were already drying up due to population decline across the Empire. Perhaps the greatest blow was the loss of Lucius Verus himself; upon his return to Rome he fell sick after a few years and became the largest victim of the Antonine Plague.

The Great Migration

Finally ruling Rome alone now, Marcus Aurelius’ mounting problems were only beginning. At the height of the Antonine Plague the first signs of the Great Migration from the North had begun to show. Barbarian tribes beyond Roman borders in Germany and the Slavic countries began to migrate en masse south and west into Roman territory. Faced with a shortage of manpower in the Legions and a lack of tax revenues in the treasury the border defenses were easily overrun.

The Marcomanni invasions were among the most serious of Roman invasions because they directly targeted Italy. Rampaging from Eastern Germany across into Gaul, the Marcomanni moved south and entered Italy for the first time in nearly 300 years. Marcus was repelling another offensive in Pannonia when he heard news that the Marcomanni had entered Italy and razed several towns. Realizing the severity of the situation he quickly shifted his focus to Italy and raised new legions to fight back the German tribes. Within a few years Italy had been purged of the invaders and Marcus decided now was the right time for a counteroffensive. Rome crossed the Danube river a few years later and launched the start of a long fight with the Marcomanni and the allied tribes. The Marcomanni counter offensive in 171 was a series of long and grinding fights across modern-day Germany. The Romans fought back and subjugated the allied tribes of the Marcomanni including the Quadi, Contini , and the Varistae over 4 years of continuous fighting. Marcus adopted title of “Germanicus” for his great victories in the north and his accomplishments were recorded in the now-destroyed Arch of Marcus Aurelius in Rome.

The counteroffensive efforts took a heavy toll on the weak Emperor’s body; the winters of Germany were punishing compared to the warm and sunny retreats of Italy and Marcus often slept late discussing battle tactics with his officers. He rejected luxuries offered by his servants instead preferring to live among his fellow soldiers in the camps which earned his army’s undying loyalty.

Your Friends Close, Your Enemies Closer

Due to the stress of the wars and the poor living conditions in the north it was at the height of the Marcomanni Wars that his weak health finally caught up to him. He contracted a form of the Antonine Plague during this period while campaigning in Germany and became very sick. The best doctors from across the Empire were called to his tent and see if anything could be done to cure him but all of them reached the same conclusion: Marcus Aurelius had at best 6-12 months to live.

Rumors of the Emperor’s illness soon began to spread across the Empire and reached the ears of his beloved wife Faustina. While Faustina was loved by Marcus and the Roman people she had begun to have doubts about her husband and her own security: years of being away from the capital left Faustina vulnerable to the political ambitions of ruthless men who were being told her husband would die soon. With Marcus’ son Commodus and the rightful heir to the Imperial throne Faustina would become a dire threat for any man who wanted to claim power for themselves. Thus with concerns about Commodus and her own safety Faustina decided to take matters into her own hands.

Meanwhile in Egypt Avidius Cassius was enjoying a long period of peace after years of fighting in Parthia. He had been rewarded by Marcus for his service in Parthia and the legions by being anointed the governor of the entire Eastern half of the Empire. However news of the Emperor’s imminent death quickly reached his ears along with a private letter from Faustina. In it she implored Avidius to rebel against Marcus and declare himself Emperor in a bid for the throne; as a reward she would promise to marry him instead and ensure the succession line for Commodus. To Faustina this was the only way to ensure the survival of her family and Avidius Cassius ultimately made the difficult choice of accepting her proposal. On paper the odds looked good: Avidius was governor of the eastern provinces of the Empire and had widespread support among Syria, Egypt and Arabia. His reputation as a war hero in the conflicts with Parthia also induced great loyalty among the eastern legions. Unfortunately his one drawback was the lack of support from the political class; many politicians and nobles swiftly denounced his rebellion and incited support for Marcus.

Avidius’ rebellion ultimately came to a quick end a few months later when a miracle occurred: Marcus had suddenly recovered from his illness without any side effects! Making matters worse for Avidius was the news that Marcus had wrapped up his Germanic campaigns with victories and was now amassing the remaining 20 legions to deal with the east. When it became obvious that Marcus clearly had the greater number of legions and had no support among the powerful Avidius’ rebellion unraveled quickly: he was murdered by his own officer and his remains sent to the Emperor.

Most would assume Marcus eventually punished his wife Faustina for her betrayal, but there was never any indication that he took action against her treachery. Marcus loved her too much and realized it was a choice made out of self preservation and love rather than spite; he chose to forgive her mistakes.

The Final War

In 177 AD Marcus launched his final war in the north. The Marcomanni decided to break the peace treaties signed 2 years earlier and along with their allies once again moved westward into Roman territory. Once again Marcus rode north from Italy and faced down his opponents in the cold winters of Germany but this time with his teenage son Commodus at his side. By now Marcus was in his late 50s and beginning to feel his age; the Antonine Plague had greatly weakened his health and the decades spent fighting and living in military camps had taken its toll.

Unlike the other Good Emperors, Marcus produced a male heir who was raised his entire life in the luxuries of the Imperial palace and destined from his birth to inherit the throne. The luxuries of Rome had spoiled him however and it was obvious he lacked the determination and work ethics of his father. Hoping to shape Commodus in to a capable ruler one day Marcus decided to bring Commodus to Germany with him in order for him to see the challenges he would face as Emperor. Over the next 3 years the Roman forces would eventually push back the Marcomanni once again, but this time Marcus could no longer fight the tide; death came for him suddenly in 180 and at the age of 58 he passed on his legacy and command of the war to his 18-year old son Commodus.

The Last Hurrah

Honor, Duty, Loyalty, and Steadfast. These are the words used to describe Marcus and his reign over an Empire threatening to explode and yet managed to hold everything together without forgetting who he was. Numerous historians credit Marcus for keeping true to his character his entire life even after surviving various tragedies and difficulties. He was physically weak but possessed a mind and heart that would not quit and thus is greatly respected among leaders even in modern times.

Marcus didn’t just leave behind a legacy of success though; he literally documented his thoughts and philosophies of life in a diary now called Meditations by Marcus Aurelius. During the Marcomanni Wars in the 170s Marcus passed the time between battles in the camps by writing his thoughts and opinions on matters of his life. When he was told he only had 6-12 months left to live his journal entries became much more spiritual; he debated topics such as Gods, forgiveness versus revenge, and the importance of being a decent human and good citizen. It was never his intention to publish his writings but upon his death his advisers found his diary and felt his wisdom too valuable to discard, thus the birth of Meditations which to this day is read by various leaders including President Bill Clinton and Secretary of Defense James Mattis.

For Rome this era was not one about conquest but rather about preservation; the Empire suffered numerous setbacks include the plague, wars, and rebellions yet managed to retain most of it’s holdings thanks to prudent governance. In between the various conflicts there were a handful of highlighted achievements such as the first contact with the ancient Han dynasty of China. In 166 there were reports from Han China of a meeting between the Imperial court and an ambassador from the Roman Empire. It’s likely this contact was planned during the Antonine years but finally realized during Marcus’ reign; the contact was significant in that it linked together two opposite worlds, but it may have also being the origin for the Antonine plague that would cause so much devastation during Marcus’ reign.

Perhaps the only mistake Marcus made was choosing his son Commodus as heir instead of adopting a more suitable one. From Nerva to Antoninus Pius, all the Emperors realized the right to rule rested on their qualifications as leaders instead of their birthright but Marcus seems to have overlooked this. Perhaps the conflict with Avidius Cassius changed his attitude and resulted in him preferring those who are closest to him such as Commodus. In any case Commodus was a severely disappointing ruler who never ingested the valuable lessons his father tried to give him. He quickly sued for an unfair peace with the Marcomanni before wasting the next 15 years in Rome fighting in the Colosseum, drinking, and descending into Megalomania before his assassination.

The death of Commodus marked the end of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty and the golden era of Rome. The decline of Rome began with the Marcomanni wars and was momentarily held back by the efforts of Marcus Aurelius; Eventually the wars opened the floodgate of disasters for decades to come and ushered in a new century for Rome:

Crisis.